Today’s blog is written by Nick Sireau the Chair and CEO of the AKU Society,

It was in 2003 that I sat down with Robert Gregory, Prof Alan Shenkin and Prof Ranganath in an office at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital and discussed where we wanted to go with the newly formed AKU Society. Robert had been living with the disease for years, while my second child had just been diagnosed.

We decided that our primary aim was to develop a treatment for AKU, but none of us realised the significant challenges that lay ahead.

For a start, we had to get a better understanding of the disease. While AKU had been identified as an inborn error of metabolism 100 years earlier, our scientific understanding of the disease was still rudimentary. Over the following years after our meeting, Prof Ranganath put in place a scientific plan for AKU, while Robert and I worked on the fundraising.

This scientific plan started with the autopsy in 2005 of an AKU patient who had donated her body to science. This allowed us to understand better what was happening inside the body of an AKU patient.

We then worked with Prof Jim Gallagher at the University of Liverpool and funded a three-year PhD student called Adam Taylor from 2006 to 2009. He developed a cell model of AKU that was crucial to prove that the culprit molecule in AKU – known as homogentisic acid – was the cause of the black pigment – known as ochronosis – that led to all the damage.

After that, we fundraised for a three-year natural history study from 2007 to 2010, which allowed Prof Ranganath to develop an AKU Severity Score Index (AKUSSI). This AKUSSI scored all the parts of the body that were affected by AKU and gave a total score that we could then track over time to see the progress of the disease.

Prof Gallagher’s team also developed from 2008 to 2011 an animal model – a mouse with AKU – which allowed us to see whether potential treatments could halt the disease.

In parallel, a group at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) under the leadership of Dr Bill Gahl was studying a drug called nitisinone for AKU. We were very interested in this too as nitisinone stops the production of homogentisic acid and should, therefore, at least in theory, have a beneficial effect on the disease.

Unfortunately, the NIH trial results that came out in 2009 showed that it had failed. Looking back, we realised it had too few patients (only 40), didn’t last long enough (only three years), and used a single evaluation criterion that wasn’t sensitive enough (hip rotation).

So the AKU Society and the Liverpool team put our heads together to figure out what we could do. Nitisinone worked wonders in the mouse model – completely stopping the disease in its tracks – and the few patients who managed to secure the drug were saying it was helping them immensely.

By then, it was 2011. We spent much of that year working on an application to the Department of Health’s Highly Specialised Services division to set up a National AKU Centre (NAC) at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital. Early in 2012, we heard that we had been successful. This meant that all AKU patients in England and Wales could come to Liverpool once per year for a whole battery of tests and get access to nitisinone off-label (without a license).

Meanwhile, our group joined forces with Swedish Orphan Biovitrum (SOBI), the company that owned nitisinone, and an expert in rare disease clinical trials called Dr Tony Hall. We created a consortium of 13 partner organisations from across Europe to carry out major clinical trials to attempt to prove that nitisinone could work for AKU patients and obtain a license. Lessons from the NAC proved crucial when designing and implementing the trials and ensuring their success.

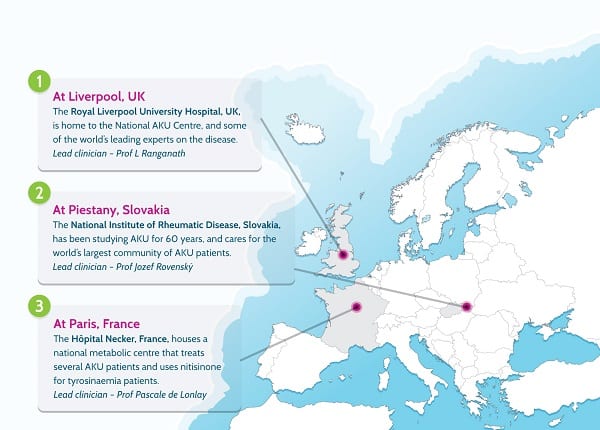

Thanks to €6m in funding from the European Commission in 2012, the consortium launched a study called SONIA 1 (Suitability of Nitisinone in Alkaptonuria 1) to find what dose of the drug could reduce homogentisic acid the most. That dose (10mg) was then chosen for SONIA 2 (Suitability of Nitisinone in Alkaptonuria 2), which was a four-year trial with 138 patients from across Europe and the Middle East in three clinical trial centres (Liverpool, Paris and Piešťany in Slovakia).

SONIA 2 ended in January, and the consortium then worked on analysing the data. SOBI announced ten days ago that the data was positive and that they would apply to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for a marketing authorisation license for nitisinone for AKU.

This is fantastic news, although the journey is far from over. SOBI expects to submit the file to the EMA in the first half of 2020. The EMA will then take six to 12 months to go through the data and decide whether or not to grant a marketing authorisation.

I would like to thank all the AKU patients who participated in the AKU clinical studies for their support. Without you, none of this would have been possible. For more information, please contact Info@akusociety.org.