The discovery of AKU

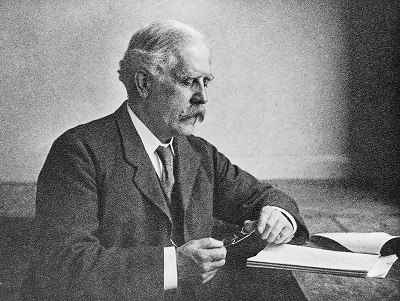

AKU was first described as an inherited disease by Sir Archibald Garrod¹ in 1902. Sir Archibald was a true pioneer – relying upon simple observations to understand fundamental aspects of human biology. He was an Edwardian doctor who specialised in what we now call, metabolic medicine.

After treating several patients with AKU, and looking at their family histories, he realised the disease followed patterns. It was quite common for brothers and sisters of patients to also have AKU; and for it to be more common in the children of a consanguineous marriage². He came to realise that AKU was somehow inheritable.

Sir Archibald knew AKU was caused by a chemical mistake (now known to be the chemical homogentisic acid), which he termed an ‘inborn error of metabolism’. While investigating the mysteries of AKU, Sir Archibald became friends with William Bateson³, a Cambridge scientist. Bateson realised AKU and its inborn error of metabolism was actually a Mendelian recessive character; a compound that was inheritable along a predictable pattern and which caused disease.

For the early 20th Century, this was ground-breaking – the ideas of inheritance and genetics were only just being formed. The discovery of DNA was still 50 years away, so there was little understanding of how diseases could follow family lines. The work of Garrod and Bateson showed that a disease could be inherited and was determined by a biochemical compound. This helped develop the idea of a genetic disease, and gives AKU its claim to fame as the world’s first genetic disease.

Sir Archibald Garrod went on to present AKU, along with three other inheritable diseases (albinism, cystinuria, and pentosuria) at a Croonian lecture⁴ in 1908. It was here that his term: an ‘inborn error of metabolism’ became known and eventually led to the creation of a medical society: the Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism (SSIEM)⁵ in 1963.

William Bateson meanwhile took the example of AKU and helped create modern genetics. He is credited with naming the word: ‘genetics’⁶ along with the well-known terms: ‘heterozygote’, ‘homozygote’⁷ and ‘allele’.⁸ In 1910, he founded a journal to help explain this new phenomenon of science, called the Journal of Genetics.⁹

Sir Archibald summed up the importance of his research into AKU and other rare disease as: “The study of nature’s experiments is of special value; and many lessons which rare maladies can teach could hardly be learned in other ways.”

While Bateson used the more concise: “Treasure Your Exceptions!”

Harwa, the AKU Mummy

Our very oldest AKU patient is a mummy called Harwa from 1500BC.¹⁰ In life, he was a doorkeeper in the Temple of Amun, the largest temple in Egypt at the time. He was the first mummy to be flown on an airplane and is currently on display at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

A Summary of AKU Research History

- 1500 BC – Earliest evidence of AKU in Harwa the Egyptian mummy

- 1584 AD – A German doctor, Dr Scribonius, describes the urine of a patient turning black when left in air

- 1859 – Dr Boedeker names the chemical that darkens urine as an “alkapton”, and therefore calls the associated disease: “alkaptonuria”

- 1866 – Dr Virchow describes the pigmentations seen in the cartilage of AKU patients and calls the process: “ochronosis”

- 1902 – Sir Archibald Garrod describes alkaptonuria as an inherited disease

- 1908 – Sir Archibald Garrod defines an inborn of metabolism, using AKU as an example

- 1958 – Dr La Du shows that AKU is caused by a lack of an enzyme, homogentisate dioxygenase (HGD)

- 1993 – Dr Pollak maps the AKU mutation to chromosome 3

- 1994 – Dr Montagutelli shows that some mice naturally develop AKU

- 2003 – AKU Society founded by Bob Gregory and Prof Ranganath

- 2008 – The US National Institute of Health conclude their unsuccessful clinical trial testing nitisinone in AKU patients (results were published in 2011)

- 2011 – Results of the first coordinated identification campaign of AKU patients in the UK

- 2011 – Dr Taylor and colleagues show the progression of pigmentation in AKU patient cartilages

- 2012 – Launch of the National AKU Centre (NAC)

- 2012 – Launch of the DevelopAKUre clinical trials, which aimed to reassess the effects of nitisinone in AKU patients

- 2012 – Dr Taylor shows AKU in mice is the same disease as in humans

- 2013 – SONIA 1 (the first study in DevelopAKUre) ends, with results confirming that nitisinone does lower HGA and setting the correct dose for future study (results were published in 2015)

- 2014 – SONIA 2 (the second study in DevelopAKUre) begins, aiming to compare the effects of nitisinone against no treatment

- 2019 – End of the SONIA 2 clinical trial and notification that nitisinone does effectively lower HGA by 99%. Sobi submit the findings to the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

- 2020 – Based on the success of DevelopAKUre and SONIA 2, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommend that nitisinone be extended as a treatment for AKU.

- 2020 – The European Commission (EC) extends the existing marketing authorisation for nitisinone use in AKU. Nitisinone receives a licence for its use in the treatment of AKU.